This is a summary of all the information he gathered there – it’s perhaps not for the general interest, but if you’re an individual or firm interested in getting involved in computing education, it could be invaluable. –– Chris

[divider type=”thin”]

On Tuesday 20th November I attended an event organised jointly by the Royal Society and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport to provide a ‘One Year On’ update on the work of the Computing in Schools Delivery Group, which is one of the four delivery groups set up by DCMS as part of their Digital Skills Partnership initiative.

It was a great opportunity to meet people who are working to improve the teaching of digital skills in schools, and to find out what’s going on in this space across the country.

This is a subject that is very close to our hearts, of course, as equipping the next generation with the right skills for the digital tech industry is absolutely crucial. There is already a predicted shortfall of as many as 3 million people with digital skills in the UK by 2030, and warnings of a “mismatch between technological advances, including automation, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning, and the skills and experience workers need to leverage these advanced tools. Technology cannot deliver the promised productivity gains if there are not enough human workers with the right skills.”1

The need for improved computing education in schools should be obvious (and it is to many), yet there are still a range of problems, from poor uptake to patchy provision, poor delivery and poor diversity. These are some of the issues that DCMS, the DfE, the Royal Society and others are trying to address, and I’m going to try to describe all the various policy initiatives mobilised to address them and and how they fit together.

Hopefully by reading this and checking out the links, you’ll be primed with enough knowledge to work out how you, whether as an individual or organisation, can add your shoulder to the wheel!

Firstly, though, here are the key points I took from the conference:

- There are a range of problems with the delivery of computing in schools, as I mentioned, but there is now a joined up and concerted effort to address them.

- The strategy is to teach ‘computing’ as a discipline, not just as a skill (i.e. “coding”).

- The flagship initiatives are the new £84m National Centre for Computing Education and DCMS’ Digital Skills Partnership.

- Industry and other organisations should try very hard to support and partner with things that are already going on, rather than ‘do their own thing’.

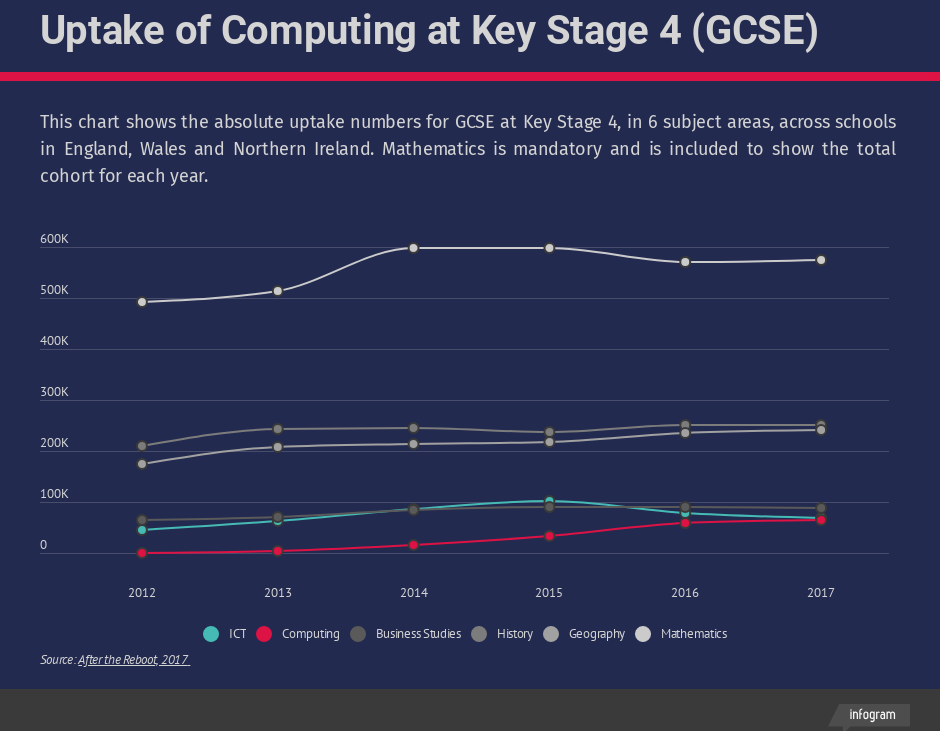

- Uptake of both GCSE and A-Level Computing is rising since its introduction but still low, even when compared to the ICT GCSE which is being phased out after this year. This is particularly true of girls and BAME pupils, and so there needs to be a strong push to widen engagement.

- There are a number of ways in which Industry can get involved, but it tends to be large corporations who do. SMEs could work closely with local schools, though, and Local Digital Partnerships and sector organisations like Sheffield Digital could help this happen.

Computing in Schools Delivery Group

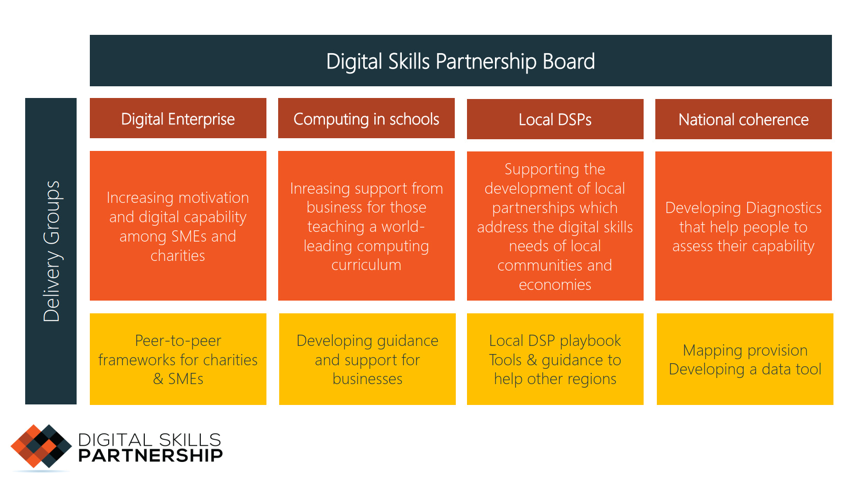

Let’s start with the Royal Society’s Computing in Schools Delivery Group itself. As mentioned, it is one of four delivery groups of the Digital Skills Partnership, the others being:

- Digital Enterprise – tasked with increasing motivation and digital capability among SMEs and charities.

- Local Digital Skills Partnerships – tasked with supporting the development of partnerships that can address the digital skills needs of communities and economies at a local level.

- National Coherence – tasked with developing diagnostics that help people to assess their capability, and mapping provision across the country.

The Computing in Schools Delivery Group was tasked with addressing the overarching problem that “many individuals and organisations do not have the digital skills required to take advantage of the benefits the internet offers,”and has three main objectives:

- Understand the landscape of industry and non-profit support for computing, computer science and digital skills associated with schools and colleges.

- Inform the efforts of industry and non-profits to maximise the impact of the support industry and non-profits are providing for young people to learn computing in schools and colleges.

- Pay particular attention to issues relating to the inclusion of girls and socio-economic disadvantage in relation to computing in schools.

One year in, their focus is on creating cohesion, improving quality and driving support for the agenda, with the principle object, now that the National Centre for Computing Education has been established (more about which later), to

“…establish a self-sustaining source of information about resources and support for Computing in Schools, with a compelling user interface that helps teachers, students and supporters find the best matches for their needs, identify gaps in provision, and drive increases in coherence, quality and support”.

They are now developing this data framework and platform outline, to share with Government and the NCCE.

Let’s just backtrack a little, though. The background to all this is the following events:

- In 2012, the Royal Society published the report “Shut Down or Restart?” – a review of computing education in UK schools.

- In 2014, the Department for Education launched a new National Curriculum for Computing, to replace ITC, with computer science as a foundational discipline.

- In 2017, the Royal Society published the report “After the Reboot“, which explored the state of play three years after the introduction of the new curriculum.

“After the Reboot”

The vision expressed in this report, and which permeates throughout the rest of the policy landscape, is as follows:

“Computer science is a foundational subject discipline, like maths and natural science, that every child should learn from primary school onwards.”

In practice, this means:

- focus on ideas, not technology – it’s not even primarily about computers!

- every child, not just geeks

- educational not instrumental – it’s not just a vocational/economic imperative

- discipline, not skill – in particular, not just coding.

The fundamental challenges they identified are as follows:

Challenge 1: Teacher Confidence and Supply

“We are introducing an entirely new foundational subject discipline into the curriculum”

But being a teacher is hard, and being a computing teacher is even harder, as everything is in flux. Making computer science a mainstream subject, including from early years, has consequences right across the educational system. Pedagogy is in the early stages, the qualifications are in constant change, there is not enough training available and it is hard to get to it. Plus teachers are often isolated – there’s no one else in the school to cover or support them.

Since 2012, only 68% of the recruiting target has been met – the lowest of all the ‘English Baccalaureate’ (eBACC) subjects.

As budgets have been cut there has been a drop in the amount of continual professional development teachers are taking, including in Computing where it is so necessary. In a survey, 26% of teachers said they had done none at all in the last year.

Recommendation:

- Government and Industry need to play an active role in improving CPD for computing teachers.

- Industry and academia should support and encourage ‘braided’ careers for staff who want to teach as well as work in another setting.

Progress made:

- The new National Centre for Computing Education will develop a training programme of CPD for secondary school teachers, as well as an A-Level support programme.

Challenge 2: Computing For All

There is low and flattening take up of GCSE Computer Science (see chart below).

No GCSE qualification yet covers the entire national curriculum.

70% of Key Stage 4 pupils attend a school where GCSE Computer Science is offered, but only 11% take the subject up.

Uptake has not yet even reached the level of ICT, even though that qualification is being now withdrawn.

Recommendation:

- Ofqual and Government should work with the learned societies in computing to ensure the range of qualifications includes pathways for all pupils.

Limited progress made:

- BCS has set up a Curriculum Committee to provide advice on content, qualifications, pedagogy and assessment methods.

- Ofqual has launched a consultation on how to assess programming skills as part of GCSE computer science.

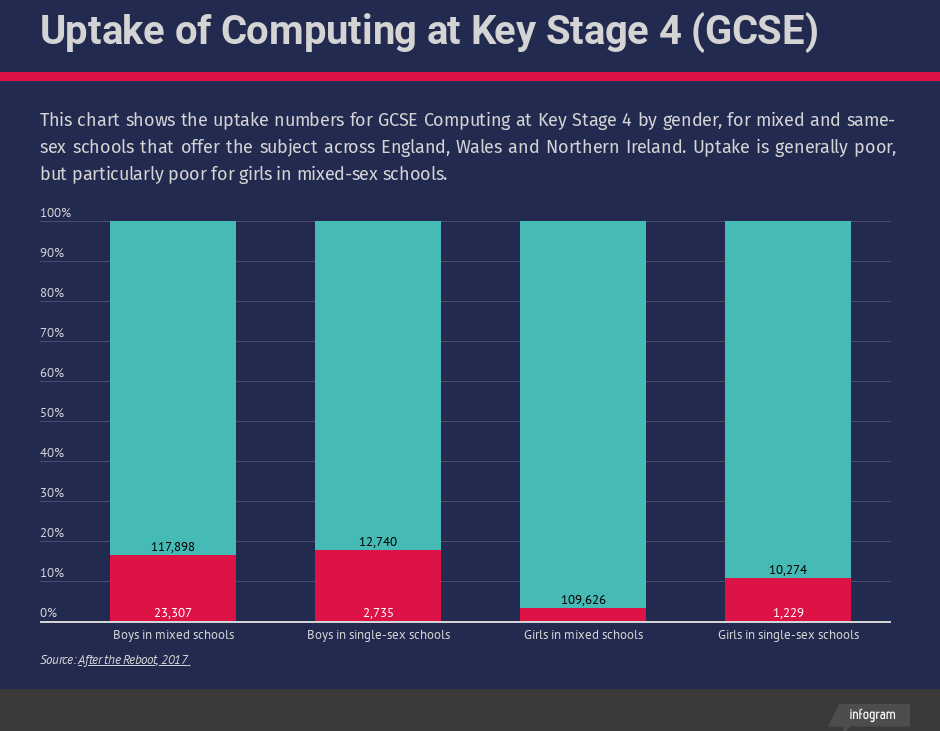

Challenge 3: Improving Gender Balance

Computer science is the most gendered STEM subject.

At GCSE, the gender balance for computing is 80%/20% male/female, while for ICT it was 61%/39%, and for Physics, Chemistry and Maths, near enough 50%/50%.

Interestingly, in schools in which at least one pupil completed a Computing-related GCSE (i.e. the school offers it), the uptake was as follows:

Recommendation:

- Government and industry-funded interventions must prioritise and evaluate their impact on improving the gender-balance of computing.

Progress made:

- £2.4m of government funding will go towards a pilot for gender balance in computing in schools.

Challenge 4: Education Research

Policy and practice should be informed by evidence, but most existing research in computing education has a focus on higher education not on school education.

The UK capacity for computing educational research is tiny, both in terms of money and people.

We need answers to questions such as:

- How do you assess computational thinking?

- Which concepts should you present in which order for which groups?

- How do we test what we want pupils to learn, not just what’s easy to measure?

- How do we teach programming as a vehicle for learning computational or informational

- thinking, rather than an end in itself?

- Should we teach via discovery or worked-out examples?

“If we are going to spend £1b on computing teachers’ salaries, using evidence to increase their effectiveness by 20% is worth £200m”

Recommendation:

- Develop a strategic plan including:

- Setting a long-term research agenda

- Stakeholders committing to this programme

- Developing a UK research capacity

- Sharing knowledge between researchers, teachers and teacher trainers.

Progress made:

- The Royal Society and British Academy published a joint report on Harnessing Educational Research, assessing the state of educational research and setting out future visions.

- King’s College London has established a new research centre in computing education connecting expertise in education, computing, robotics and related disciplines.

The National Centre for Computing Education

The Department for Education has committed £100m to this initiative across England, Wales and Northern Ireland (of which £84m is allocated for England), on a four-year programme between 2018 and 2022, and with the intention of providing the much needed support for computing teachers in all key stages.

In November this year they announced that the new centre will be run by a consortium consisting of The Raspberry Pi Foundation, STEM Learning and the British Computer Society.

The initiative consists of four specific ‘lots’.

Lot 1– The NCCE & Network

- 40 Secondary-school Computing Hubs.

- Central repository of resources

(this is where the delivery group’s work now connects). - Evidence-based and quality-assured CPD.

- Links with relevant industries.

- Free, targeted support for priority schools.

- Evidence base for effective theory and practice to be further developed.

Lot 2 – Training programme GCSE

- At least 40 hours of training, GCSE

- DfE standards

- Includes initial assessment and certification on completion

- Free for teachers and schools

- Includes supply-cover costs

Lot 3 – A Level Support

- Develop knowledge-rich resources

- Deliver face-to-face roadshows and master-classes for pupils

- Deliver support to A-Level teachers

- Free for all A-Level pupils and teachers

- Targeted at schools and colleges that offer A Level Computer Science

Lot 4 – Gender Pilots

- A pilot programme to identify effective approaches to improve gender balance in computing education and increase girls’ participation in GCSE and A-Level Computer Science.

(This is still under procurement)

In addition to these lots, the Centre is also seeking to establish a network of 10 regional delivery partners in England, details of which are on the STEM Learning website (we are aware that Sheffield is bidding for one of these).

Industry Engagement

The consortium is also seeking engagement from industry and has identified 5 ways in which businesses can get involved:

Specifically, these are:

Volunteer

Get involved with current programmes including:

- STEM Ambassadors

- Barefoot

- Code Club

Enrichment

Provide advice and inspiration:

- Careers inspiration

- Work placements

- School and college visits

Content

Provide resources:

- Computing educational material

- Subject knowledge expertise

- Students, parents, teachers and schools

- Help shape relevant skills for industry

Funding

Donate to Project ENTHUSE, which is a partnership of government, charities and employers that provides bursaries for teachers’ Continual Professional Development

Funding for existing initiatives and programmes

Advocacy

Tell policy makers why computing education matters to your business!

Further Info on Programmes

It’s important to have some clarity on the programmes mentioned above and others – here’s a brief overview of the most significant ones:

Raspberry Pi Foundation

The Foundation runs a range of programmes for both in-school and extra-curricular education. I’m hoping to put together a separate post explaining their programmes in more detail, including how to get involved locally.

Meanwhile, here’s a breakdown:

- Learning resources and projects

- Raspberry Jams – community-run digital making events

- Code Clubs – volunteer-run after-school clubs for 9–13 year olds

- Coder Dojos – volunteer-run public coding clubs for 7–17 year olds

- The MagPi – the official Raspberry Pi magazine

- Hello World – the magazine for computing educators

- Astro Pi – competition to run code on one of the two Raspberry Pis on the ISS

- Coolest Projects – global project showcase being held in Manchester in March 2019

- Picademy – online teacher training

Barefoot

Barefoot is a programme run by Computing at School (CAS), part of the British Computer Society, with sponsorship from BT. Its mission is to provide good quality teacher training in computing and computational thinking to primary school teachers nationwide.

Since being established in 2015, it has helped train teachers who have then provided lessons to over 2 million pupils, and is looking to greatly expand its offering and reach.

Key to this is that there is now significant evidence that computational thinking helps pupils in a range of other areas of learning. This is a really important message to get across to policy makers and school heads.

In 2017, BT produced a report in conjunction with Mori Ipsos, called Tech Literacy: A New Cornerstone of Modern Primary School Education. It showed that teachers reported improvements in problem solving, collaboration, numeracy and literacy.

STEM Learning

STEM Learning, (STEM being science, technology, engineering and mathematics) are another partner of the National Centre for Computing Education, and provide a range of programmes:

- Teaching resources

- Continual Professional Development for teachers

- A directory of enrichment activities and services

- A network of independently-run STEM Clubs

- The STEM Ambassadors programme, which are volunteers from a wide range of STEM related jobs and disciplines

Computing at Schools

In addition to the Barefoot programme, CAS also run a raft of programmes to support teachers and schools, including the provision of resources at Primary and Secondary levels, certifications, research and self-review tools, etc.

They have also developed a network of schools and teachers who are focused on teaching computing, with regional hubs to bring these communities together all over the country. Collectively, this is the CAS Community, and there are CAS Community meetups currently active in Sheffield:

- The Sheffield & South Yorkshire Primary CAS Hub

- The Sheffield & South Yorkshire Secondary CAS Hub

I’m sure both of these would welcome support from employers!

Employer Initiatives

We also heard from several major tech companies about their programmes.

Cisco Computing for Schools and NetAcad

Cisco provide a range of resources to help teachers introduce networking into their lessons, via their Networking Academy (NetAcad), including using the Packet Tracer tool to help kids understand what the Internet really looks like ‘under the hood’.

See Cisco Computing for Schools

ARM Schools Programme

ARM provide a range of training materials at University level, but also have an internal programme that encourages their employees to volunteer in Code Clubs and engage with schools around tech.

They also sponsor and host the Cambridge CAS Community.

Microsoft – TEALS Programme

In the United States, Microsoft has been running a programme called TEALS (Technology Education and Literacy in Schools) since 2009. They do not currently run it in the UK, but they presented here to highlight the fact that there might be some lessons and approaches that could be applied by others here, especially initiatives like STEM Ambassadors that help professionals engage directly with schools.

For instance, TEALS trains volunteers and pairs them with schools and teachers, and they commit to one year and a minimum of 200 hours of engagement. They have also learned little things like ensuring the engagements are held first thing in the morning, so the volunteers can then go straight to work afterwards and not lose too much time in the day.

Morgan Stanley

Morgan Stanley has a corporate social responsibility mission to reduce inequality in programming, informed at least in part by their own research. They support the Girls Who Code movement around the world, and convene regular women in tech events.

They have been stepping up their programme in the UK, and now work with five schools in London. That includes a Muslim all-girls school where take up has been very good, though they’ve had to negotiate some interesting cultural sensitivities, especially with male volunteers. They appear to be building great knowledge in this area.

—-

Right that was it! I also had many conversations with people at the event, including someone who said that they had heard that Sheffield is a big centre for digital tech (which was gratifying).

If anyone wants to talk about Computing in Schools, or digital skills in general, do come along to a Geek Brekky on a Friday morning, start a conversation in the #-skills channel on the Sheffield Digital Slack Community, or drop us a line 🙂

Footnotes

- “The Global Talent Crunch“, Korn Ferry, 2018 ↩